Gefährdende Spiele

The Irretrievably Lost

‘We were growing, and sometimes impatient,

to grow up, half for the sake of those

who’d nothing left but their grown-upness.

Yet, when alone, we entertained ourselves

with everlastingness: there we would stand,

with the gap left between world and toy,

upon a spot which, from the first beginning,

had been established for a pure event.’

Rainer Maria Rilke

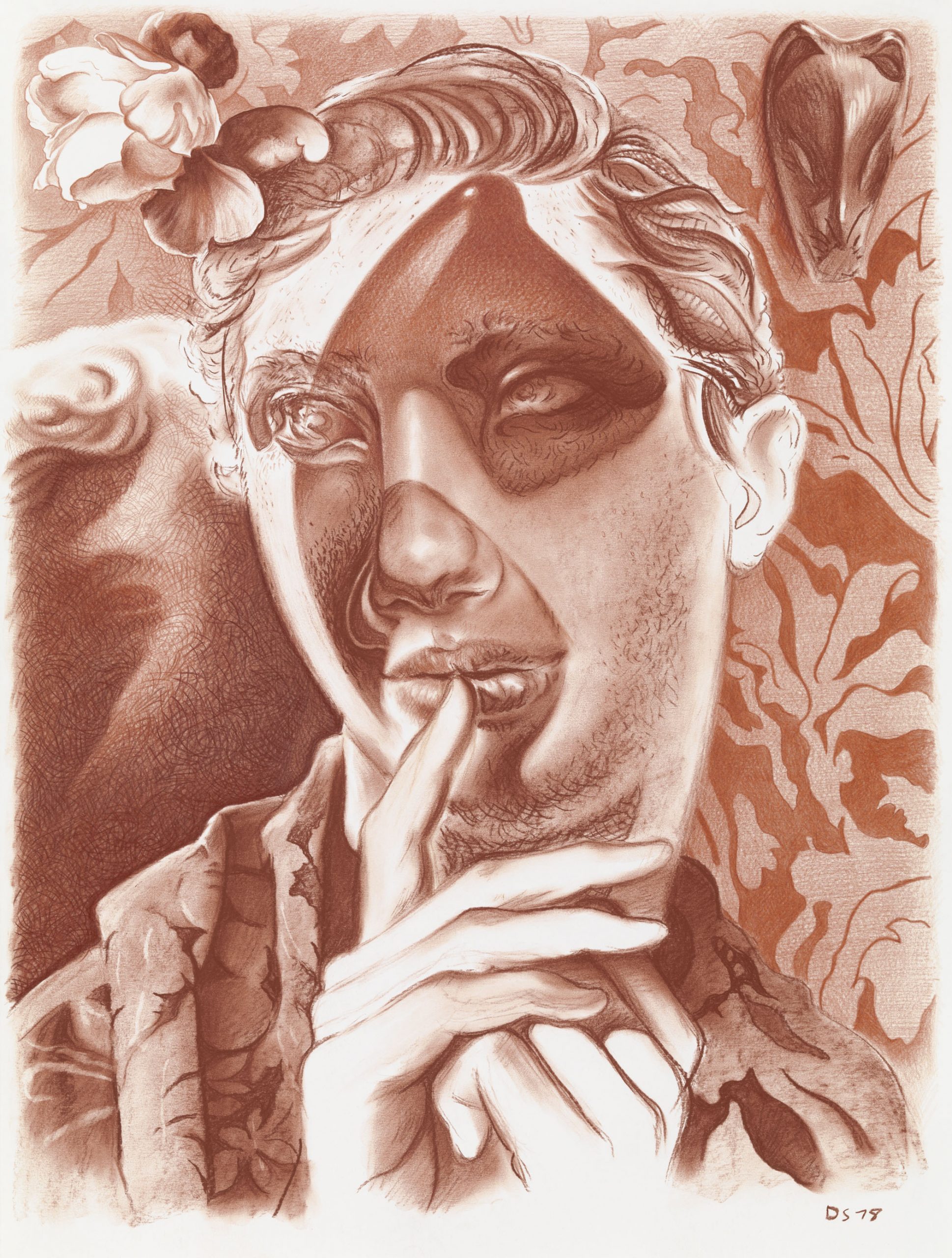

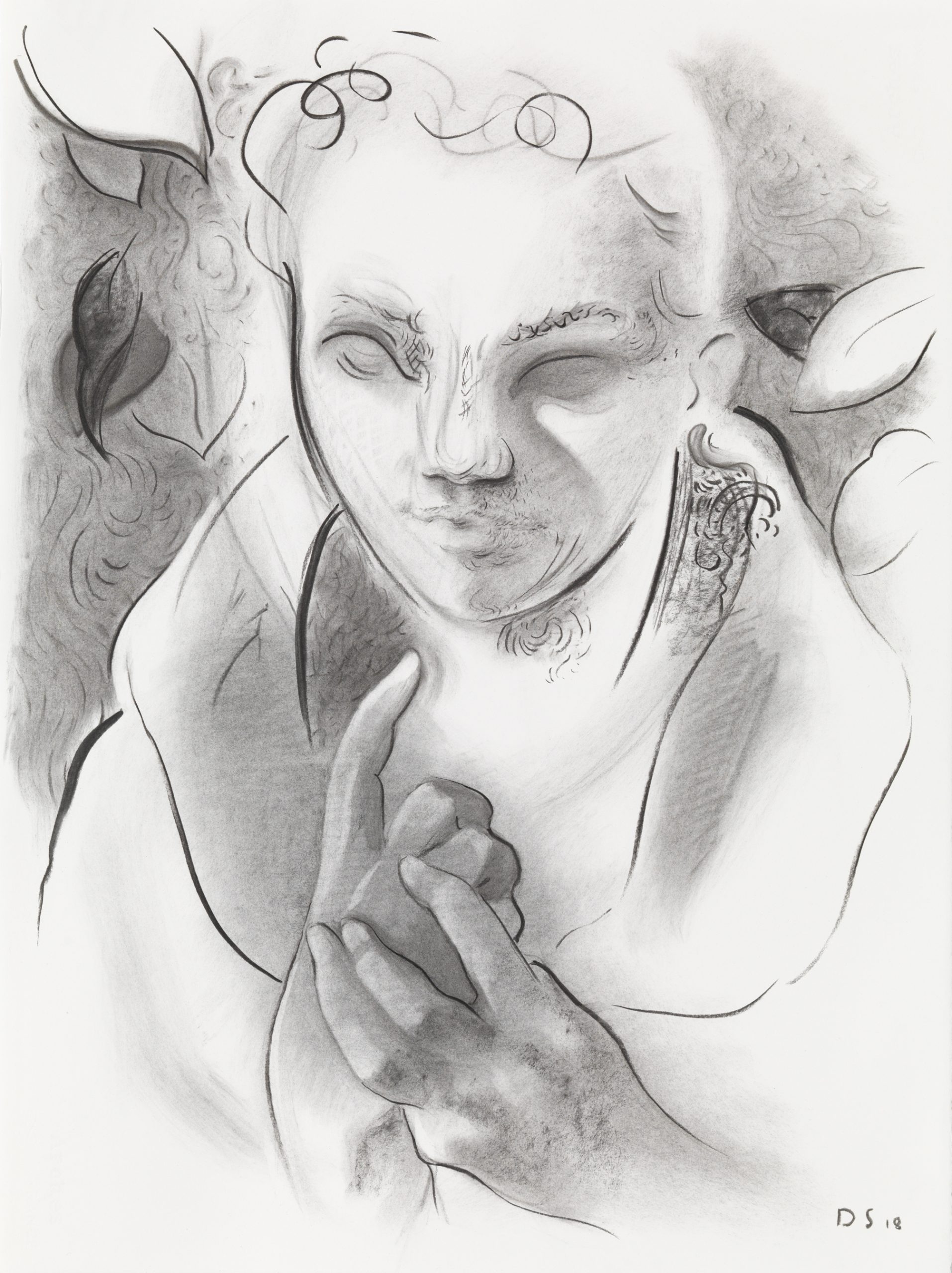

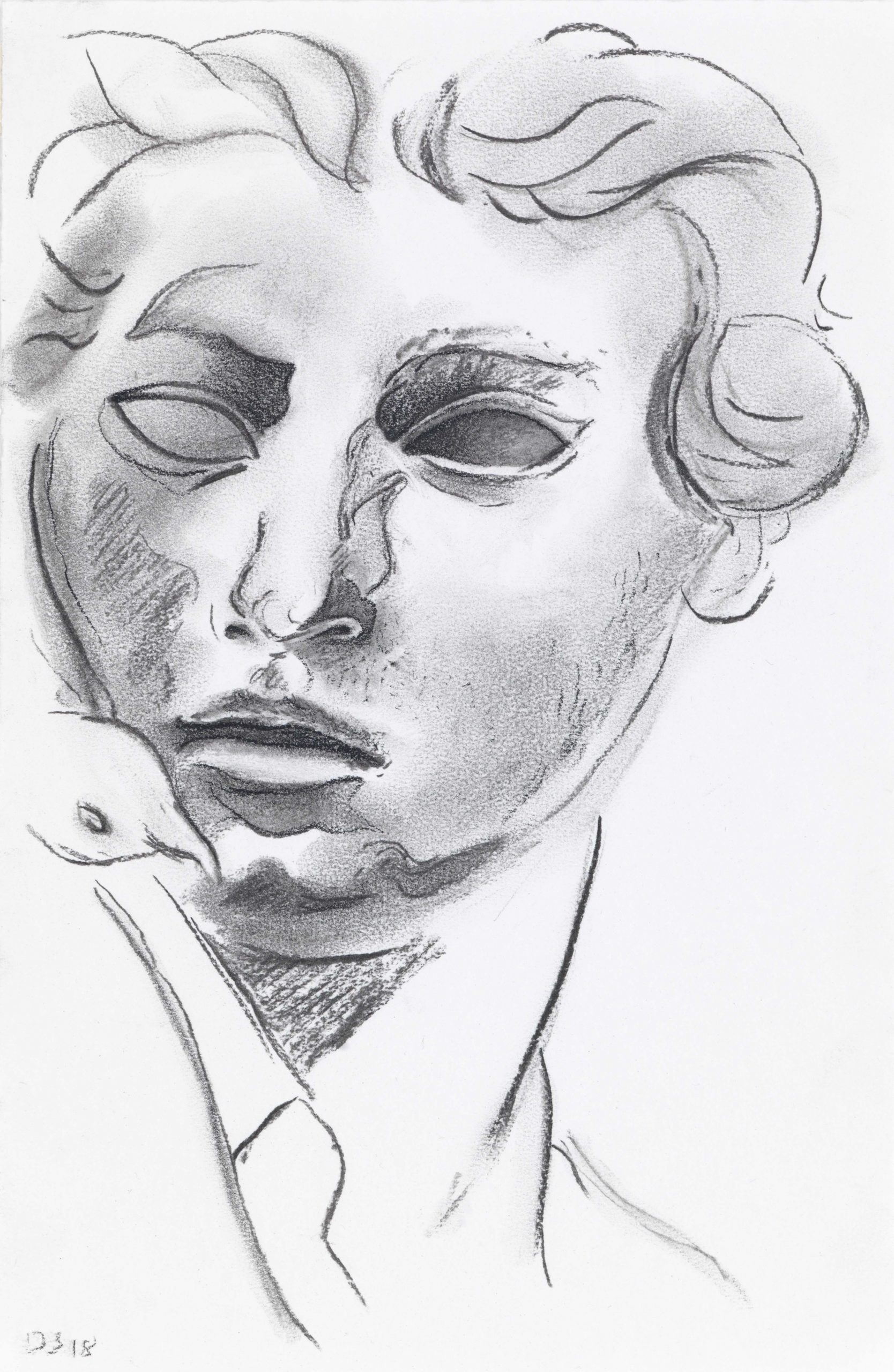

Like the poet, painter Dennis Scholl sets out in search of lost youth. Adolescence represents a point of rupture, a time of transformation and pain, but also of curiosity. This tense phase, a metamorphosis, also occupied Rainer Maria Rilke. In his longing for the lost, he created romanticized spaces of memory. The lyricist meticulously examined this welcoming of adulthood and farewell to childhood – the beginning of the end. ‘O hours of childhood, hours when behind the figures there was more than the mere past, and what lay before us was not the future.’ The time as a teenager is looked back upon with a yearning regret and a constant longing to experience feelings from this period again. To see oneself as pure as a child is a commonly expressed desire, but an unspoiled youth is an illusion, a dream like Arcadia, one that is misinterpreted in its apparent infallibility. ‘Et in Arcadia ego’ , even in Arcadia there is death, even in childhood there is desire. These transfigurations are nostalgic visions of a past happiness, which subsequently remains unattainable forever. Memory alone keeps it alive for a while.

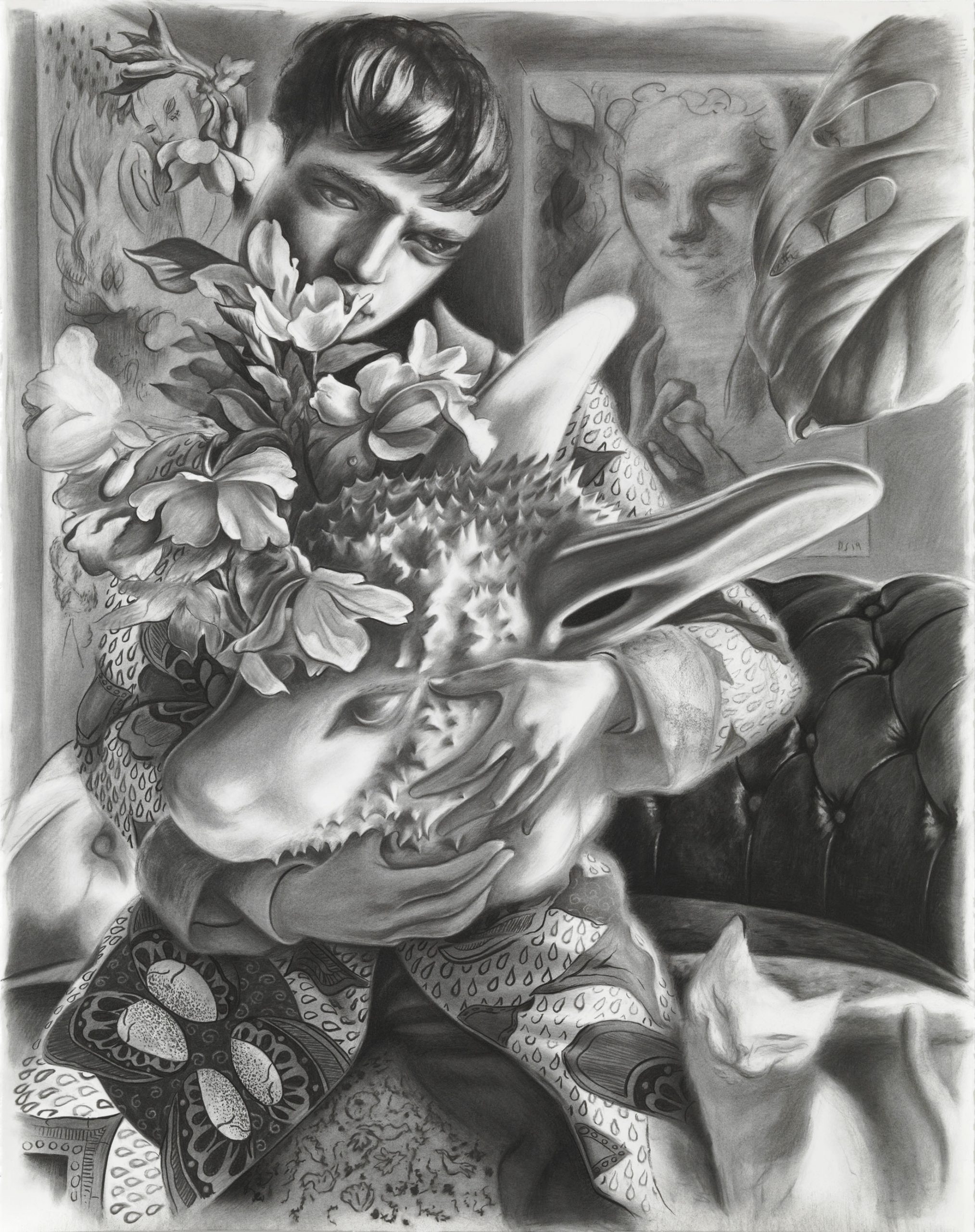

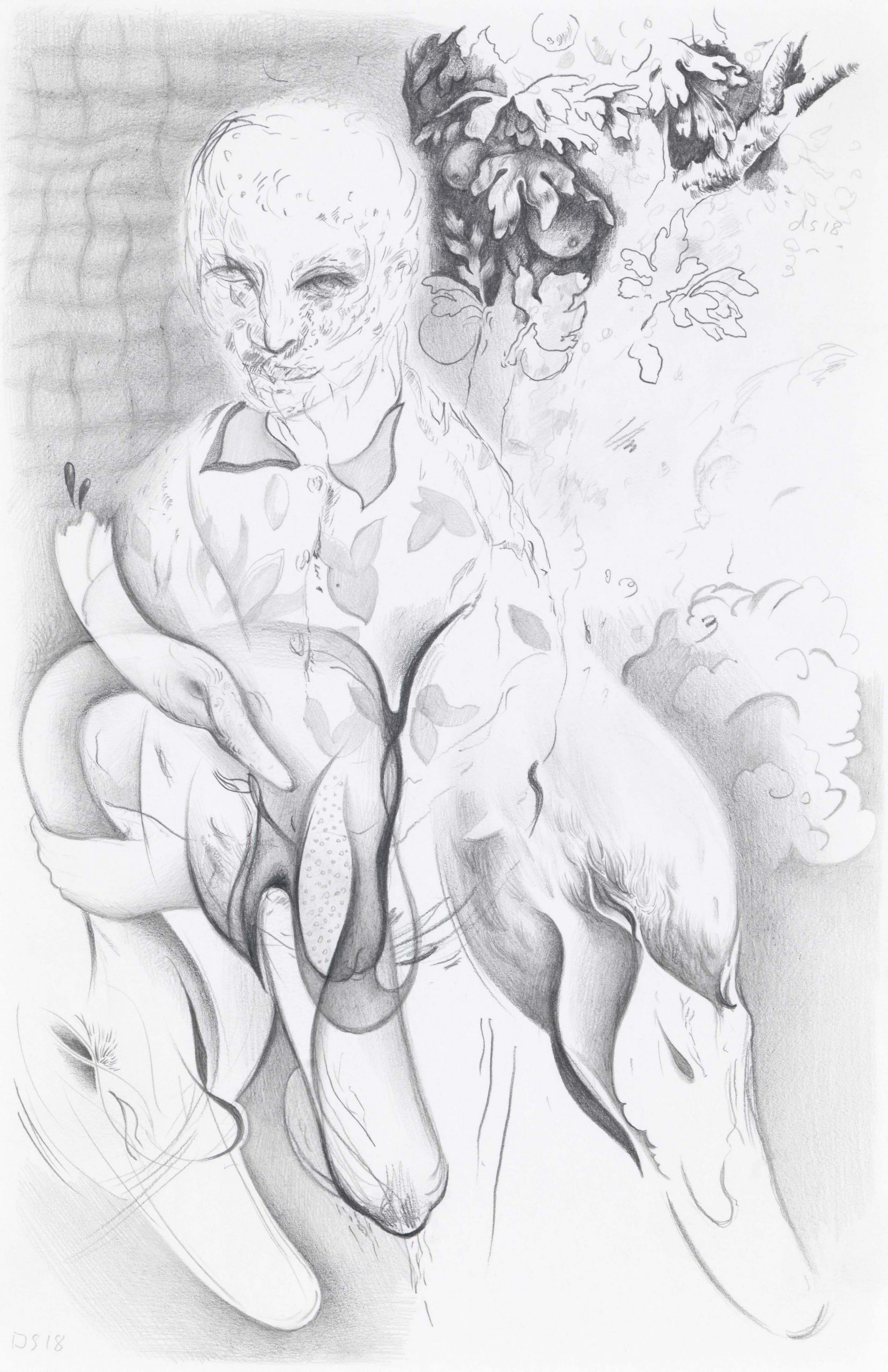

The painter Balthus, Rilke’s protegé, also dealt thematically with the myth of youth. However, he tried to expose this fallacy of a virtuous childhood. His paintings, whose main characters often depicted minors, are characterized by a mysterious and latently threatening aura. Contrary to many viewing habits, Scholl’s works lack a direct moment of shock. The pictures instead are undergirded by a subtle sexuality and violence which seems paradoxical given the naïvety of the artist’s subjects. As with Balthus, this ambivalence provides an opening into the abyss of uncertainty. It is via this space that the images are held in suspense.

The tension between beauty and violence, youth and death persists throughout Scholl’s oeuvre. Behind the veil of harmlessness, a fateful knowledge awaits the viewer, a vehicle through which everything is shaken. ‘Who’s not sat tense before his own heart’s curtain? Up it would go: the scenery was parting’. Yet the works themselves do not offer much ground for orientation: the protagonists are often neither clearly male nor female, and the possible interpretations are endless. In this way, Scholl entrusts the audience with the task of telling the story themselves. The eventual individual interpretation reveals far more about the viewer than about the artist. A part of one’s self is always projected into what is seen. In the conception of art, values of experience are thus judged meaningfully by character-forming attributes and by a knowledge gained in the past. The observer is appointed an accomplice. Like emblems, Scholl’s paintings become allegories that not only convey a certain idea, but also serve as catalysts for a deeper exploration of one’s own certainty.

So, who are Scholl’s scenes staged for? For the youthful figure in Ort der Gefährdenden Spiele (Place of Endangering Games) who looks out knowingly whilst smiling from behind the tree, while his or her counterpart chastises the third figure? What role does the viewer play in front of these pictures? Particularly in the large-format oil paintings, blurred elements create a barrier between the subject and the observer, who, as if looking through a spy hole, becomes the ‘Peeping Tom’ of these forbidden scenes. As a cautious master builder of an idiosyncratic world, Scholl has been providing us with selective insights into interpersonal events and encounters for years. His works are an invitation to visit these ‘Places of Endangering Games’.

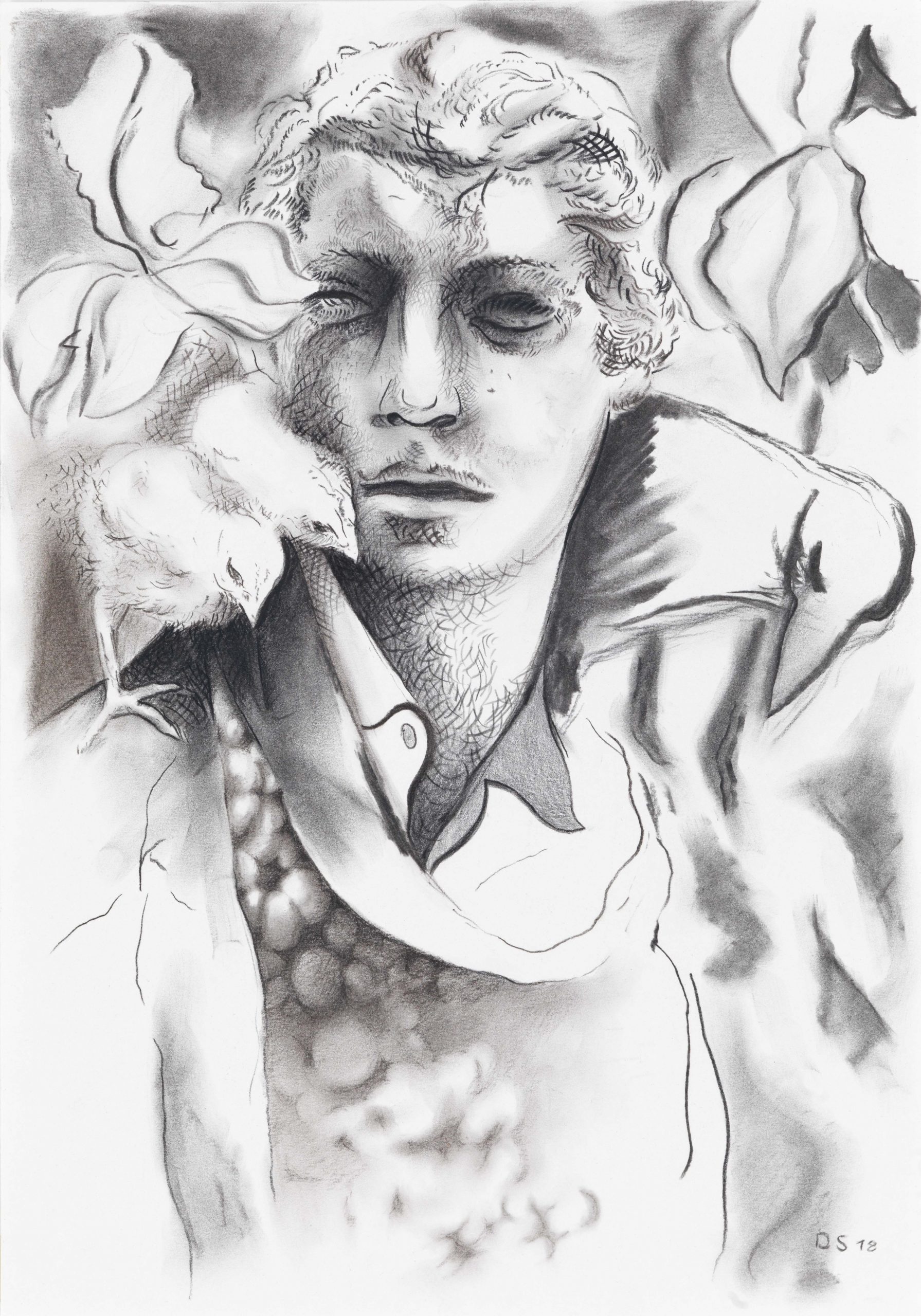

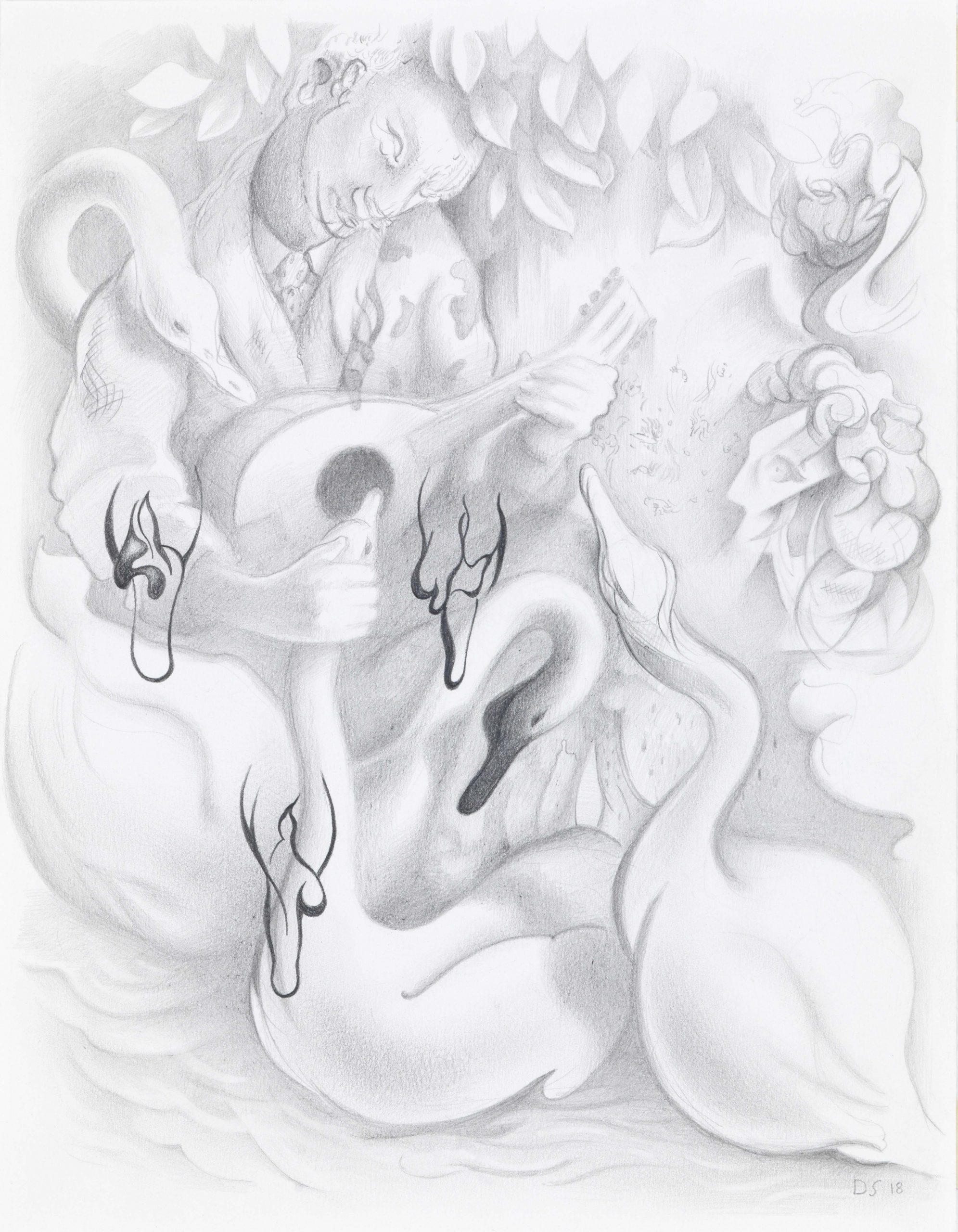

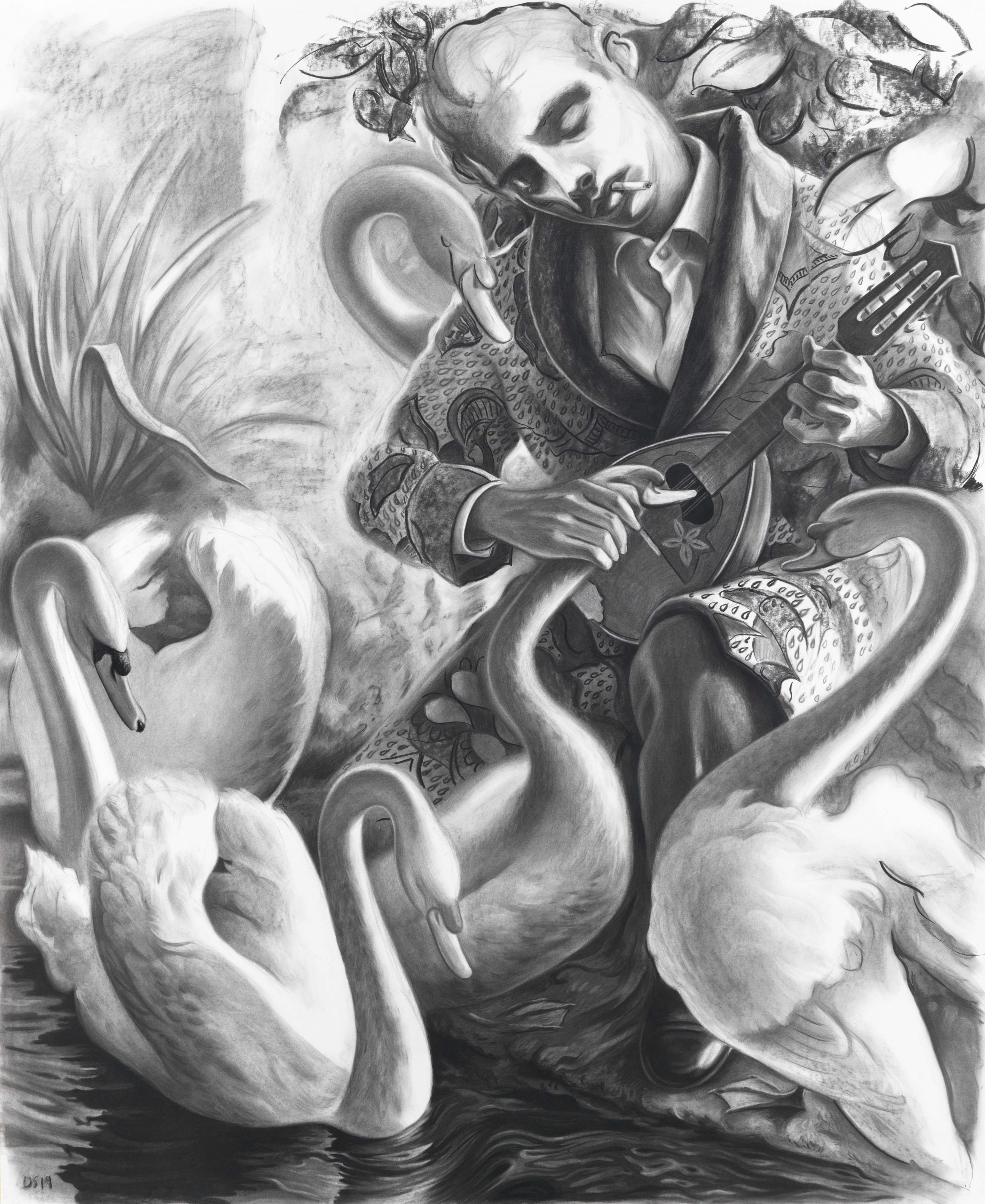

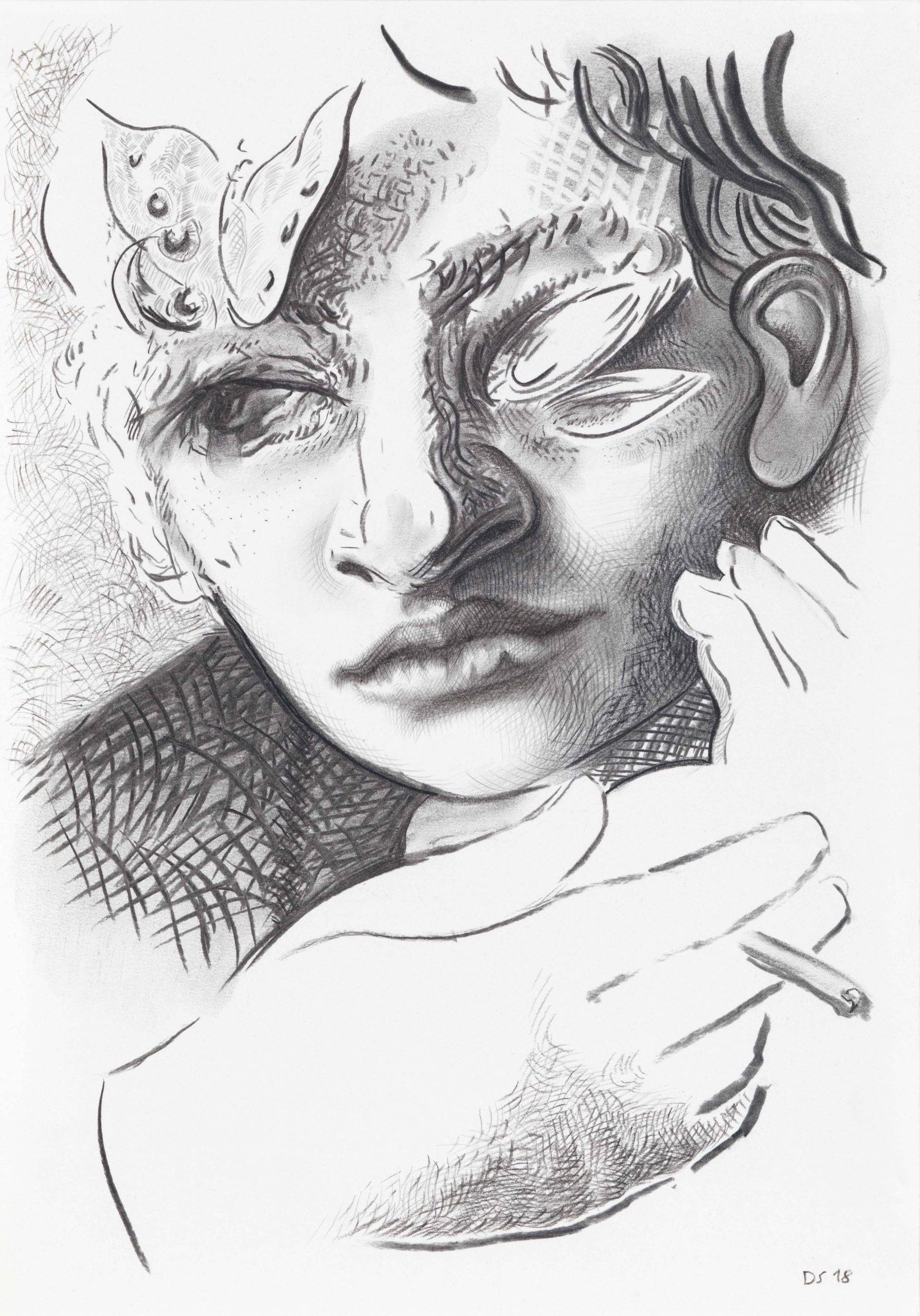

The former draughtsman became a painter. The new materiality changes the way the story is told but the narrative remains the same. This metamorphosis makes a gradual continuation of each tale possible. Like the transformation of the larvae into the butterfly, from child to adult, the artist’s transition from drawing to painting can be experienced for the first time in this group of works. For Scholl, this development led from pencil to crayon and is now unfolding into oil painting. The artist treats the paint almost graphically, gently and with a feeling for each line and stroke. It is used translucently, and tones and materials are modelled through numerous layers. Scholl also picks up various techniques and materials in the paintings themselves – such as the paper cut in Das Lied der Vermutungen (The Song of Suspicions), which winds down from the hand of the seated figure, while the severed head of a stone sculpture lies on the wooden floor.

But just as childhood is a part of every life story that cannot be negated, drawing is also indispensable for Scholl’s artistic process. He by no means turns his back on this technique and though he has embraced painting, remains a draughtsman. However, there has also been a change within this practice, a further metamorphosis. In their openness and interplay with various forms, styles and techniques, Scholl’s drawings reveal a new understanding of the medium. The artist seems to have outgrown the narrowing cocoon of the pencil. This liberation is expressed in ecstatic sweeps and loose movements, in their unbridled expression and the exploration of new possibilities. These also include the game of modelling and removing. The method of constant creation and subsequent annihilation leads the viewer through the images of this group of works. This concept manifests itself most clearly in the smoke of the cigarettes once exhaled, and thus made visible, it already dissolves again. Some figures have only a single elaborate, spirited eye, while instead of the second there is nothing but an abstract emptiness. Then again, the artist contrasts withered, dying leaves next to spring-like, verdant green plants. In Die Rast des Boten (The Rest of the Messenger), the swan is brutally strangled in order to play the most delicate tones on the mandolin. In the charcoal drawings this idea finds its most concrete expression in the traces of wiping away and redrawing; once laid lines can still be recognized but have been overdrawn by new ones.

What remains is an inkling of what has been. Without the past there is no present and the future lies in the vanishing of the Now. Scholl follows this trace into childhood and makes memories visible. He reveals that tragedy and cruelty are hidden behind every glorifying memory. His works serve as a mirror for self-reflection and as a reminder for an open contemplation of things. To emphasize human consciousness as one who already sees and knows its end – echoes what Rilke was also ultimately seeking:

‘We’ve never, no, not for a single day,

pure space before us, such as this which flowers,

endlessly open into: always world,

and never nowhere without no:

that pure, un-superintended element one breaths,

endlessly knows, and never craves.‘

Text by Nicola E. Petek. For the catalogue accompanying the exhibition at Galerie Michael Haas, 2019.